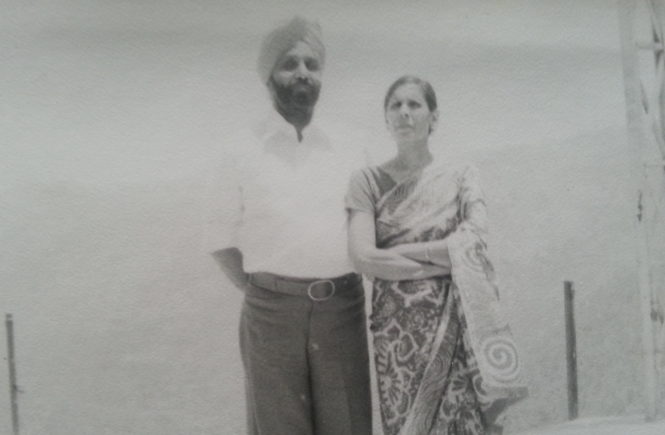

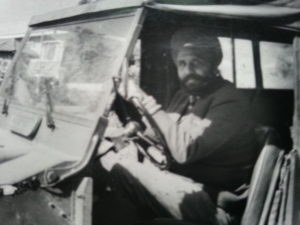

Our dad died of a jeep accident, just nine kilometres from our place: Whispering Winds in Kandaghat (Shimla Hills) (Please read: ‘Home Is Where The Hear Is – Kandaghat In Shimla Hills’) on the 1st of May 1984. Tomorrow, would be the thirty-fifth anniversary of that fateful day, a Monday, when he was on his way to Shimla to receive his promotion orders as Additional Director of Horticulture, Himachal Pradesh. On the same evening, he and our mom were to travel by train from Kalka to Shimla to be with us at Bombay for my wife’s first delivery.

When the phone-call came about his demise, I thought it would be dad telling us (for the nth time) about their programme (as was his habit). Our world was totally shaken.

The place whereat his jeep went down the hill at Kiarighat is the unlikeliest of the places for an accident: broad and level road with proper parapets. It was rumoured that he was put to death because of a number of reasons; the chief one being that he was fighting it out with the government against discrimination.

Racial, religious and regional discriminations are rampant in India even though, ostensibly, we portray ourselves as being proud of our pluralism. When I was small, in the Himachal town of Mandi, because of my long-hair (as a Sikh) I was subjected to constant jeering by my school mates. Some of it was just annoying whereas at times it was vulgar (“Jatta, O jatta, teri bhen da tatta” (O Jatt, balls to your sister) and dangerous (they tried to bury me alive once and I was saved at the last-minute when my father crossed the burial spot).

Dad too had to face similar wrath by those who feel that Punjabi speaking should stay in Punjab, Bengalis in Bengal and so on.

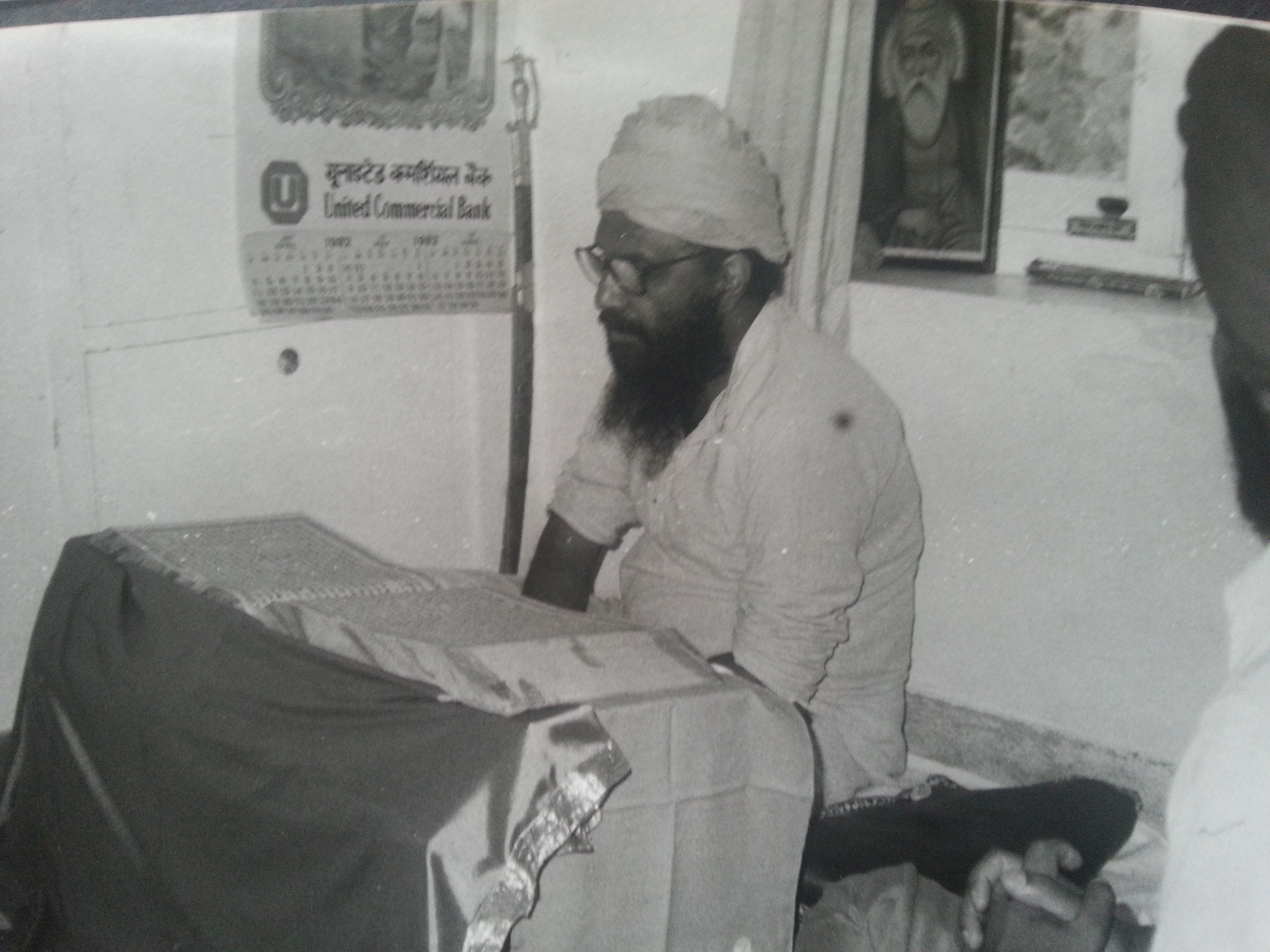

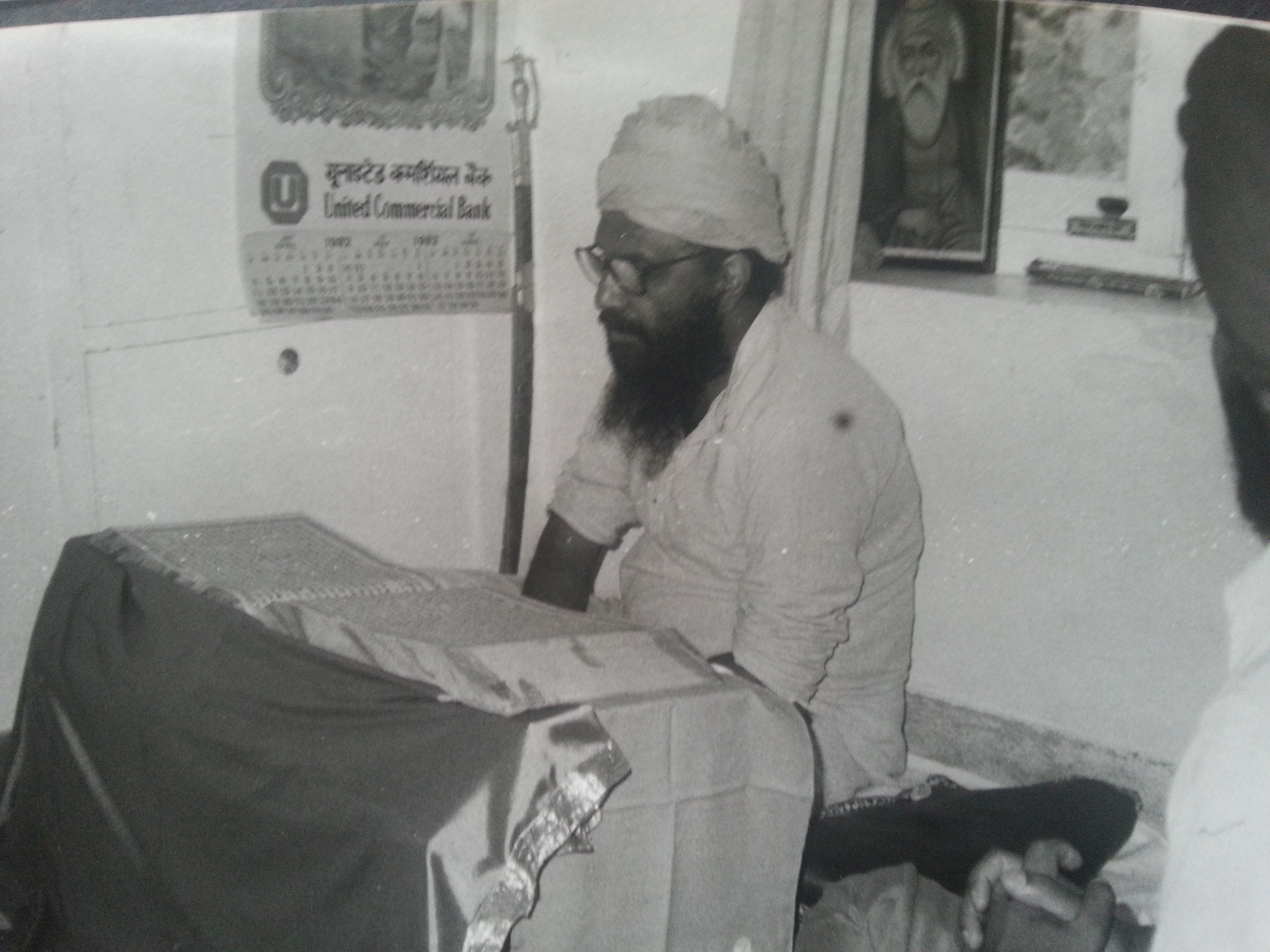

Our mom died last year on the ninth of August; she having outlived dad by nearly three decades. She used to have the Bhog (Completion of the entire reading) of Sri Guru Granth Sahib on the First of May every year. She would start reading a few months before. This time, it was left to me to do a Sadharan Paath (Daily reading of SGGS for about ten days) in his memory. It was five to six hours of reading at my speed. What kept me going was the fact that dad, just a few years before his demise, did an Akhand Paath (Non-stop reading of the SGGS until completion) on his own with my mom and I providing him short breaks only for ablutions:

Paath was not the only thing that we learnt from our dad. Here are a few of those things (not in any particular order):

1.  You Are As Rich As You Think You Are. Dad was a self-made man and hence never had too much of money. He was also a very proud man; he would rather give than take from others. Even at that, he gave the impression of being many times richer than what he was. He told me that his father had given him this blessing when he was still in college, “Mani, tu bahut paise kharchen” (Mani, you should spend a lot of money). My dad told me that he thought of his dad crazier than what I would have ever thought of my dad. It was because with his meagre resources, his father was giving him blessing to spend even more. It is only in later life that my dad understood his dad’s blessing: that he could spend only if he had and he could spend as long as he had. Grandad was an intellectual and a God-fearing man. What a brilliant blessing he gave my father and to credit to the latter, he followed it in toto. Here is on the tenth page of my favourite book: Sri Guru Granth Sahib ji (Raag Goojri Mehla 5):

You Are As Rich As You Think You Are. Dad was a self-made man and hence never had too much of money. He was also a very proud man; he would rather give than take from others. Even at that, he gave the impression of being many times richer than what he was. He told me that his father had given him this blessing when he was still in college, “Mani, tu bahut paise kharchen” (Mani, you should spend a lot of money). My dad told me that he thought of his dad crazier than what I would have ever thought of my dad. It was because with his meagre resources, his father was giving him blessing to spend even more. It is only in later life that my dad understood his dad’s blessing: that he could spend only if he had and he could spend as long as he had. Grandad was an intellectual and a God-fearing man. What a brilliant blessing he gave my father and to credit to the latter, he followed it in toto. Here is on the tenth page of my favourite book: Sri Guru Granth Sahib ji (Raag Goojri Mehla 5):

kaahay ray man chitvahi udam jaa aahar har jee-o pari-aa.

Why, O mind, do you plot and plan, when the Dear Lord Himself provides for your care?

sail pathar meh jant upaa-ay taa kaa rijak aagai kar Dhari-aa. ||1||

From rocks and stones He created living beings; He places their nourishment before them. ||1||

When dad died, we had next to nothing and yet we never forgot dad’s example of being rich.

2. You Should Fear No One Except God. How could dad do it even though he often had people and circumstances ranged against him? It is because he maintained a clear conscience. He was in the horticulture department and we had a lot of fruits and fruit products coming home. I used to think that these were probably perks of the profession. After my dad died I found, amongst his papers a file in which he had been billed for everything that came home and receipts of having paid. He was a terror when he dealt with people (rigid on his principles) and yet other than being harsh whilst demanding standards and efficiency, he never did any harm to anyone. He had the same way of dealing with his superiors as with his juniors and I have seen and heard his superiors fearing him. Dad stood alone combating all his problems. It was only just before his death that I was saddened to know what he was going through. He never gave the impression that he had any problems. He often sang and I know that he fervently believed in this hymn:

2. You Should Fear No One Except God. How could dad do it even though he often had people and circumstances ranged against him? It is because he maintained a clear conscience. He was in the horticulture department and we had a lot of fruits and fruit products coming home. I used to think that these were probably perks of the profession. After my dad died I found, amongst his papers a file in which he had been billed for everything that came home and receipts of having paid. He was a terror when he dealt with people (rigid on his principles) and yet other than being harsh whilst demanding standards and efficiency, he never did any harm to anyone. He had the same way of dealing with his superiors as with his juniors and I have seen and heard his superiors fearing him. Dad stood alone combating all his problems. It was only just before his death that I was saddened to know what he was going through. He never gave the impression that he had any problems. He often sang and I know that he fervently believed in this hymn:

Jis ke sir upar tu swami,

So dukh kaisa paave?

O Lord, one who is under Your protection (one who considers You to be above himself),

How can he experience any suffering (in life)?

Coincidentally, in the Yaad Kiya Dil Ne (my Music Group on Facebook) Group’s Annual Meet at Kandaghat, on 14th April this year, Pammi sang my dad’s favourite hymn that was penned by Sri Gobind Singh ji when he was in Machhivara Forest, alone and separated from everyone, whilst fighting against Aurangzeb:

Mithr piaarae noo(n) haal mureedhaa dhaa kehinaa ॥

Thudhh bin rog rajaaeeaa dhaa oudtan naag nivaasaa dhae hehinaa ॥

Tell the beloved friend (the Lord) the plight of his disciples.

Without You, rich blankets are a disease and the comfort of the house is like living with snakes.

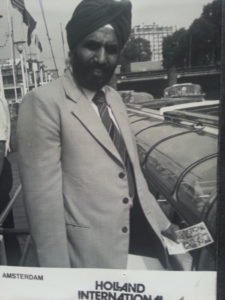

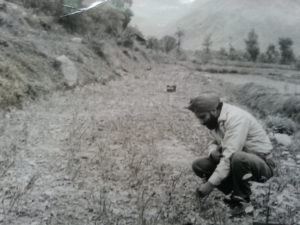

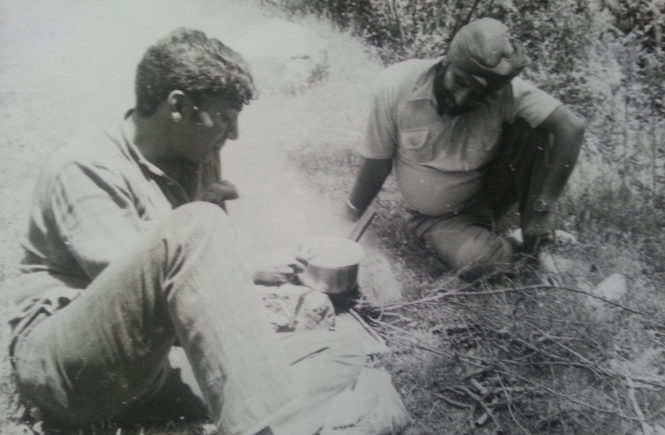

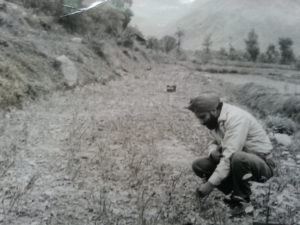

3. Nothing Is Impossible. It has been 35 years after his demise and yet I have never come across a man who believed in this more. If his heart was set on doing a thing, no one could stop my dad. When he constructed the house at Whispering Winds, Kandaghat, the local Panchayat declined to provide water connection so far away from the main town of Kandaghat (we are exactly one and half kilometres away and that’s why our village is called Ded). Undeterred, dad went about laying a pipe from the village Bawri (a water resource in the hills) and next day we had all the water we wanted. This connection is our main source of water even 39 years later. Following our example, the other houses have made similar connections. Fortunately the Bawri has enough for everyone.Two of the very good examples of following in the footsteps of our dad were provided by my younger brother JP. In Shimla, he had just finished learning roller skating when next he broke the world-record of non-stop skating. Later, he had just learnt bicycling when he bicycled all the way from his school (Lawrence School Sanawar) to Kanyakumari.

3. Nothing Is Impossible. It has been 35 years after his demise and yet I have never come across a man who believed in this more. If his heart was set on doing a thing, no one could stop my dad. When he constructed the house at Whispering Winds, Kandaghat, the local Panchayat declined to provide water connection so far away from the main town of Kandaghat (we are exactly one and half kilometres away and that’s why our village is called Ded). Undeterred, dad went about laying a pipe from the village Bawri (a water resource in the hills) and next day we had all the water we wanted. This connection is our main source of water even 39 years later. Following our example, the other houses have made similar connections. Fortunately the Bawri has enough for everyone.Two of the very good examples of following in the footsteps of our dad were provided by my younger brother JP. In Shimla, he had just finished learning roller skating when next he broke the world-record of non-stop skating. Later, he had just learnt bicycling when he bicycled all the way from his school (Lawrence School Sanawar) to Kanyakumari.

Dad won’t take No for an answer and always found a way out.

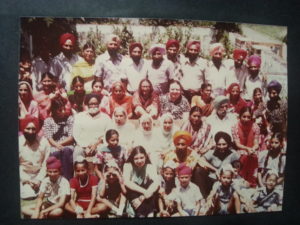

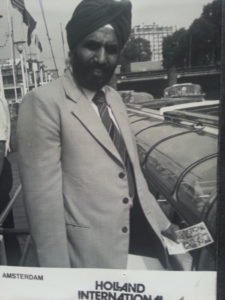

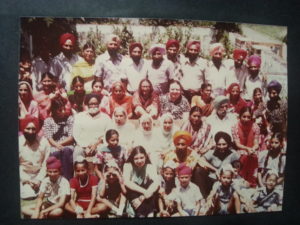

4. Family And Friends Are Important. Dad invariably took us along with him for picnics, get-togethers, visits etc. Even when he was hard on us, we knew he never planned anything without us. Similarly, he made friends easily and stood by them in their hour of need. He was a great party man and offered the best hospitality to all who visited us irrespective of their status in society. I recall that mom would be publicly embarrassed by him in case she wouldn’t have offered the best available at home to the guests. His sincerity and loyalty towards the larger family and towards his friends often saw him through situations that could be messy.

4. Family And Friends Are Important. Dad invariably took us along with him for picnics, get-togethers, visits etc. Even when he was hard on us, we knew he never planned anything without us. Similarly, he made friends easily and stood by them in their hour of need. He was a great party man and offered the best hospitality to all who visited us irrespective of their status in society. I recall that mom would be publicly embarrassed by him in case she wouldn’t have offered the best available at home to the guests. His sincerity and loyalty towards the larger family and towards his friends often saw him through situations that could be messy.

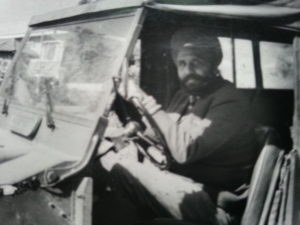

5. Never Lose Your Sense Of Humour. Dad had a sense of humour that never lift him. He would make fun of serious situations and consciously made them smaller than they were. He would often laugh out loudly and include everyone around him in the lighter side of the situation. Conversely, he would make some very insignificant (to us) things look very big. For example, whilst travelling with him, we had learnt after several shocks, that if he would suddenly say, “Oh, eh ki hogeya?” (Oh, what has happened now); we should know that he hadn’t run over something or that the vehicle had developed serious defect, but that we had suddenly crossed a milk-bar without stopping.

5. Never Lose Your Sense Of Humour. Dad had a sense of humour that never lift him. He would make fun of serious situations and consciously made them smaller than they were. He would often laugh out loudly and include everyone around him in the lighter side of the situation. Conversely, he would make some very insignificant (to us) things look very big. For example, whilst travelling with him, we had learnt after several shocks, that if he would suddenly say, “Oh, eh ki hogeya?” (Oh, what has happened now); we should know that he hadn’t run over something or that the vehicle had developed serious defect, but that we had suddenly crossed a milk-bar without stopping.

6. Never Mix Work With Pleasure. Dad’s full energies and time were utilised on whatever he was engaged in. If he was working, there was no way he could be expected to give less than his best. Conversely, when enjoying, work was farthest from his mind. I remember after I became a commissioned officer in the Indian Navy, I came home on my first leave unannounced, hoping to give him a pleasant surprise. Mom wasn’t at home. I kept my baggage with the neighbours and walked to dad’s office some five kms away. Dad was happy to see me, hugged me, and offered me a glass of fruit-juice. The time was about 2 PM and dad said we would go back together at the end of the day. Within about ten minutes, he was so busy in his work that he had forgotten all about me. It was only when we were going back home that he exchanged pleasantries.

6. Never Mix Work With Pleasure. Dad’s full energies and time were utilised on whatever he was engaged in. If he was working, there was no way he could be expected to give less than his best. Conversely, when enjoying, work was farthest from his mind. I remember after I became a commissioned officer in the Indian Navy, I came home on my first leave unannounced, hoping to give him a pleasant surprise. Mom wasn’t at home. I kept my baggage with the neighbours and walked to dad’s office some five kms away. Dad was happy to see me, hugged me, and offered me a glass of fruit-juice. The time was about 2 PM and dad said we would go back together at the end of the day. Within about ten minutes, he was so busy in his work that he had forgotten all about me. It was only when we were going back home that he exchanged pleasantries.

7. Always Be Kind To The Lower Staff. Dad was large-hearted and invariably forgave his staff for even their worst lapses as long as these were honest mistakes. He would slang them until cows came home but I had seen this for myself that the staff had no doubts in their minds that he loved them. On the day that he died, rather than the driver picking him up from our home, dad was to pick up the driver since his house was between our house and Shimla where dad was headed. He was killed just a km short of the driver’s house.

Right now, even after thirty-five years of his demise, we still feel discrimination in our place. Someone who has flagrantly encroached on our land appears to be favoured by the authorities in the garb of being a local. However, with our dad’s principles that we inherited, we bat on regardless and fear no one but God.

Tomorrow, when we have the Bhog of the Sri Gur Granth Sahib, exactly how our mom used to do it for so many years after dad went away, we shall pray that we never falter on those principles that made dad what he was.

Dad, we still miss you but you are still alive with us.

You Are As Rich As You Think You Are

You Are As Rich As You Think You Are 2. You Should Fear No One Except God

2. You Should Fear No One Except God 3. Nothing Is Impossible.

3. Nothing Is Impossible.  4. Family And Friends Are Important

4. Family And Friends Are Important 5. Never Lose Your Sense Of Humour.

5. Never Lose Your Sense Of Humour.  6. Never Mix Work With Pleasure.

6. Never Mix Work With Pleasure.