If you have ever voted in any election in India, you are familiar with how they mark your index finger, extending from lower part of nail to skin of the finger, with indelible ink. This ink is produced in a company called Mysore Paints and Varnish Limited, the only company in India authorised to do so. After about 30 to 40 days, there is no trace of this indelible ink left and you are ready to vote again. Joining politics (or for that matter any other profession) has, at best, that so called indelible mark that stays a short time and then you are ready to be a turncoat and align your thinking and conduct with some other vocation.

However, one truly indelible ink is the one with which you are pronounced a fauji. It stays with you forever. Your mannerism, style, conduct and even way of thinking undergo permanent and indelible changes. You are not the same person anymore. As was penned by Rudyard Kipling in his famous poem ‘If’, the day you become a fauji, you suddenly become a man:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise:

…………………..

…………………..

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

Son? Many a times I view things from my father’s point of view; how it must have been for him to send me to fauj knowing (I know that he knew) that, like those planes on trans-Atlantic flights, once I cross over that crucial point-of-no-return, I am gone forever. He knew that he was not sending me to a new profession, but a new life, family and world.

As I penned in ‘Indian Navy Is The Only Life That I Have Known Or Seen’, it is a totally different life, family and world. Even after you hang your uniform and boots (so as to say), you are left with only one way of problem solving, reacting and dealing with anything at all. I have spent, for example, nearly six years in India’s largest corporate company and even those six years didn’t change the way I dealt with problems. On the other hand, I applied fauji solutions to everything, albeit with a little modification.

My dad never joined the armed forces but for all practical purposes he was a fauji. I remember during my boyhood days, my sister and I were always in constant fear of him. Whenever we would hear his Monga (a German vehicle just like the Army Jonga) approaching (in the silence of the hills the engine noise of the Monga was distinct), we would be like dahine-se-sajj (by the right, dress). As soon as he would be with us, the inquisition would commence starting with if we read the newspaper; and, if we did, what was the national and international news.

He was also punctual like a fauji and always kept appointments dot on time. During my sister’s marriage, for example, he nearly cancelled the time when the baraat (marriage party) didn’t reach on time. Our relatives had tough time calming him down with “kudi daa maamla hai” (It is your daughter’s life).

LIke a fauji he was forever young (jawan) and physically fit.

But, the foremost manner in which he was like a fauji was his problem solving abilities and those related to quickly getting to the core of the matter rather than beating around the bush. The other day a senior colleague wrote a piece in one of the publications about how Indians keep discussing problems and solutions but never get to implementation of any of them. Dad was different. He would do before you could count till ten and in many cases, like a typical Punjabi, do the thinking later.

So, after my initial training in the Naval Academy at Cochin (now Kochi), I joined the Cadet Training Ship INS Delhi. I was excited because it was a dream come true to be finally on board an Indian Naval Ship. To give him credit, dad had tried his utmost to stall my becoming a fauji. He constantly bombarded me with how he was preparing me to become an IAS/IFS officer and that sane, intelligent and respectable people should steer clear of becoming fauji. Dad didn’t succeed and I eventually became what I wanted to become: an Indian Navy officer. However, the present leadership of the country and the current attitude of our countrymen are now succeeding to keep as many young men and women from joining the armed forces as they can with their relentless indifference and disrespect.

Anyway, after the tough routine of my first day on the cruiser Delhi, I burnt the midnight oil in writing to him a detailed letter about how my dream had finally come true.

I wrote about the history of Delhi. I wrote that when she was with the British, she was named HMS Achilles and had taken part in the famous Battle of the River Plate (close to Argentina) with HMS Ajax and HMS Exeter (a battle in which they were pitted against the might Admiral Graf Spee and others). I wrote that in 1948 she joined the Indian Navy as first HMIS Delhi and then INS Delhi on India becoming a republic on 26th Jan 1950. I wrote that she starred in the 1956 movie ‘The Battle of the River Plate’ with John Gregson, Anthony Quayle, and Peter Finch. I wrote that whilst I was in the Naval Academy at Cochin, on one of the afternoons I had seen the movie. I recounted an interesting anecdote that in one of the aerial shoots, the complete scene of Delhi as Achilles was shot with the other ships when the Director Michael Powell frantically asked for the scene to be done again. It was because even though all hatches were kept closed, at the crucial moment, one Sikh sailor emerged from one of the hatches complete with beard and turban.

I also described the 6 – guns of the ship and how she helped to liberate Goa on 18th Dec 1961. I wrote about walking on the quarterdeck of the ship whereat history invariably walked with me and my chest exceeded (in later years, Narendra Modi’s) 56 inches when I walked past the 6 – inch guns with their brass plaque describing the famous battles she had fought and won.

I described the forever humming of the engines and the generators and my bunk in the cadet’s mess. Whilst describing the ship in relation to me, I even quoted the poet:

The guns you fired were my guns,

And the lives you lived were mine

The arrival of this letter at our house Whispering Winds, Kandaghat was described to me by my mom. After dinner, dad and mom slipped into the bed and dad (as he was wont to do) asked my mom to read the son’s letter to him. She read slowly and deliberately all the way from Dear Dad to …….. lives you lived were mine ….. with lots and love and regards to mom and you….yours affectionately Ravi.

After she had finished, dad lay there thinking for sometime and then asked her to read the letter all over again. Mom, thinking that dad had made peace with my having become a fauji and was full of deep fatherly love and high respect for the history and heritage of the Indian Navy, read it the second time, more slowly and and with added emphasis. After finishing she awaited his response. And sure enough, the response came. This was it:

“Kinne paise mang rehya hai?” (How much money is he asking for?)

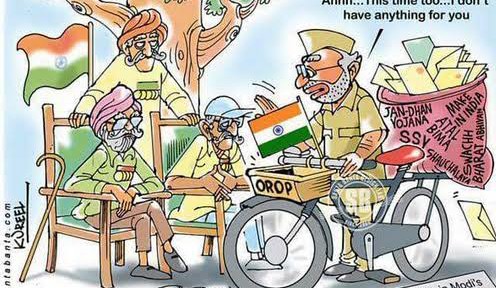

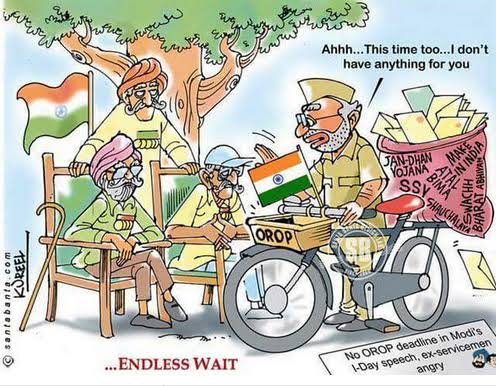

PS: If dad was the Finance Minister of NaMo, instead of Arun Jaitley, the faujis won’t have to beg on their knees endlessly for OROP.